2014-03-11

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a type of anxiety disorder that can occur after an individual has experienced an extreme emotional trauma involving the threat of injury or death. It is not known why traumatic events cause PTSD in some people but not in others, however, factors such as genes, emotions, and family setting may all play roles.

PTSD and combat related PTSD are complex and debilitating conditions that can affect every aspect of a person's life. Jessica Miller (MPhil Cantab) of Bournemouth University has developed a project researching PTSD, navigation and genes, with which she is undertaking a PhD (supervised by Dr Jan Wiener) and is collaborating with UCL (Prof Chris Brewin). As part of the study, participants will be screened for brain injury, depression, psychosis, pain, and alcohol consumption. Symptom severity will be assessed for childhood trauma adult trauma exposure/ PTSD (and CR-PTSD). Cognitive questions will further investigate the impact of childhood trauma on development and navigation behaviour.

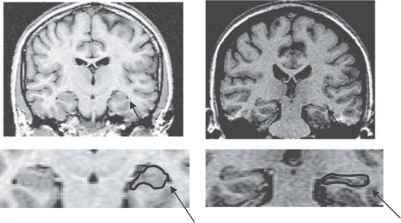

The hypothesis being tested with this research is that individuals who carry the val66met gene and who experience childhood adversity are more likely to suffer worse PTSD after exposure to trauma as adults than those who do not carry this gene. These same individuals are also less likely to prefer (and/or perform well on) hippocampal-dependent navigation strategies.

Jessica and the research team expect to collect a total of 150 DNA samples of both individuals suffering from PTSD and controls. Participants range in age from 18-50 years to control for the impact of aging on the hippocampus. To date the team has collected 8 DNA samples via the mail and 50 samples in the field. The DNA test being utilized to analyze the samples is a SNP genotyping assay for the val66met polymorphism in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene as a marker of neuronal integrity in the hippocampus. Jessica chose saliva-based DNA collection with Oragene because of the non-invasive, simple to use approach which allows easy sample collection in the field or at home. The Oragene/saliva samples could be sent by post for remote collections without need for specific insurance or special medical packaging. In addition, no medical expertise is required to take the saliva samples and the self-collection kits mean participants can provide the sample when it is convenient for them and their personal space is respected. While this may seem a minor issue, it is especially important for those research participants who still suffer the effects of unprocessed trauma.

The hypothesis underpinning the study has already been published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience and Jessica and the research team hope to publish initial data as a pilot study into the role of BDNF in trauma and spatial processing within the next year. Her group will also analyse the data to demonstrate effect sizes which may serve as a sufficiently robust evidence base for further larger cohort studies. The evidence from this project will be used to apply for central funding for ongoing research, potentially with the National Health Service (NHS) and the Ministry of Defence (MOD). Looking ahead, the team hopes to establish the first genetic connection between the PTSD and navigation in the brain.

We wish the research team at Bournemouth University the best of luck with this important area of research and look forward to updates on their progress.